Early Equality: 19th Century Activists

Women have been fighting for equality with men in America since the Revolution. Writing to her husband in Philadelphia at the Continental Congress in 1776, Abigail Adams asked the founders to give women greater legal powers over themselves and their property. If they did not, she warned, women would “foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

Adams expressed her revolutionary sentiments in private, but just twelve years later, British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft put similar thoughts into print in A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1792. She argued that women’s inferiority was a product not of nature but of unequal education, and that women’s fundamental rights were the same as men’s. Here in Connecticut, the Litchfield Female Academy (founded in 1792) initially taught a standard curriculum, but gradually took up Wollstonecraft’s challenge to teach Latin, Moral Philosophy, Logic, Rhetoric, and Natural Philosophy, in addition to embroidery, music, French, and other “feminine” topics. Following on trend, the first women’s colleges in America opened in the 1830s.

At the same time as women were gaining a foothold in education, they were also stepping into the public sphere to speak out against slavery and for temperance. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton became friends and allies in London at the first World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, where they were kept from speaking on account of their gender. Convinced by this and other similar experiences that they needed to organize independently of other causes to fight for women’s rights, Mott and Stanton met with Mary Ann McClintock, Martha C. Wright, and Jane Hunt and planned the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. This was the first convention for women’s rights in America.

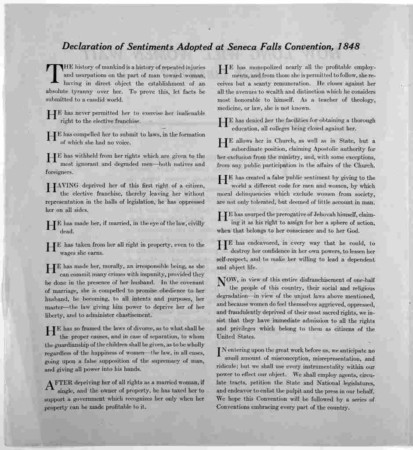

At Seneca Falls, 68 women and 32 men signed the Declaration of Sentiments, which Stanton and the others modeled on the Declaration of Independence to assert that “all men and women are created equal.” The Declaration included a list of sixteen grievances. Among them was the fact that women could not vote.

From the 1850s onward, Susan B. Anthony and other women toured the nation giving speeches and holding conventions for women’s suffrage. During these decades some women, like Anthony in 1872, defied the law and voted in presidential elections. One woman ran for president as the Equal Rights Party candidate. This was Victoria Woodhull. Nominated by other parties, she ran again in 1884 and 1892. In 1878, women even got a bill introduced in Congress that would eventually become the 19th Amendment.

Continuing education programs and social and civic clubs provided spaces for women to meet and work together, and further popularized equal rights and suffrage in the later 1800s. Wilton residents Jane Merwin and Marion Olmstead benefited from these trends, earning diplomas from a Chautauqua Institution in the 1890s. Chautauqua lectures often advocated suffrage, temperance, child labor reforms, and other populist measures.

Women’s suffrage advocacy in these years may not seem like the rebellion threatened by Abigail Adams in 1776, but for the day it was radical. For the first time women were speaking in public, wearing bloomers or half skirts over loose pants, breaking the law in civil disobedience campaigns, proposing their own legislation, and symbolically challenging men for the highest powers in the land.